Articles - The First GB Internal Airmail Contract

Copyright

© 2022 Robert Farquharson All Rights Reserved

-

British Internal Airmails of the 1930’s

The First GB Internal Airmail Contract

By Bob Farquharon

Edmund ‘Ted’ Fresson

Ernest Edmund Fresson was born on September 20th, 1891 in Wickford, Essex with his two brothers and two sisters. Fresson first became interested in aviation in 1907 when Louis Bleirot, Henri Farman and others were conducting experiments with their home-built planes while the Wright brothers Orville and Wilbur, were giving advanced exhibition flights in France with their biplane. His interest in Aviation was heightened in 1909 when on holiday in Minster-on-sea he watched the Short brothers experimenting on their own aircraft design and a group of enthusiasts doing ‘long hops’. In 1911 after leaving school, he joined a firm of Far East merchants and was sent out to Shanghai in China. It was a baptism of fire as China was in the middle of a revolution and young Fresson experienced much killing and bloodshed. In 1914 he contracted Typhus and nearly died. His firm put him on the indispensable list, and he was not allowed to enlist until 1917 when he heard of openings in the RFC being conducted in Los Angeles. By a stroke of luck, the RFC interviewer also attended Framlingham college and remembered Fresson. He was sent for flying training in Toronto in a Curtiss JN4 and on the 13th November 1917 he undertook his maiden solo flight. After qualifying as a pilot, he received further training at Fort Worth and was eventually posted to a small airfield at Holt where he carried out coastal patrols for U-boats. In the Summer of 1918, he was struck down by Spanish Flu and was seriously ill in the RAF hospital in Hampstead. He was demobbed in June 1919 and in July of the same year married Dorothy Cumming. In September 1919 Fresson was providing joy riding flights but the railway strike stopped him completing his flying tour. He needed to get the plane back to Cambridge before they left for China, but the authorities would not let him draw any petrol. Eventually he reached a compromise and agreed to take several days of mail to Cambridge, thus flying his first airmail! In October 1919 he returned to China, and did not return until 1927 and in 1928 joined Berkshire Aviation, a joy-riding circus based in Shrewsbury, Shropshire. He became great friends with the chief pilot at Berkshire, Lance Rimmer and they agreed to form their own joy riding company for the following year which would be called the ‘The North British Aviation Company’. It was registered in January 1929 with headquarters at Hooton Park Airfield, Cheshire. They started with two Avro 504k’s bought from the Beardmore Flying School at Renfrew which had closed down. They flew the aircraft back from Renfrew to Hooton on the 5th February and after several weeks of overhauling the planes and their motor’s they commenced business on the 29th March 1929. The first year of trading was successful but they felt that the company would be more profitable in 1930 if it was split into two with each pilot taking on his own area. Decisively for his future career, Fresson’s area was to be Scotland. Clearly in 1930 Fresson was looking for various landing sites and had his first brush with the law. The Aberdeen Press and Journal of the 2nd October 1930 reported that “FIELD NOT “LICENSED.” Aeroplane Pilot’s Offence in Morayshire. A fine of £2 was imposed at Elgin Sheriff Court yesterday on Ernest Edmund Fresson, aeroplane pilot, drove End House, Northwood, Middlesex, for using a grass field on the farm of Cassieford, Forres, as a place of landing and departure, which place was not licensed by the Secretary of State, contrary to the Air Navigation (Amendment) Order. “ Fresson recounts that it was when he was routing in the North of Scotland for joy riding sites that the need for an air service to the Orkneys came to him. The plan was to go as far North as Kirkwall as most that far North had never seen an aeroplane, and these virgin territories were normally the most profitable. He first visited Kirkwall in April 1931 with Miss Pauer landing in a field near Kirkwall. The plane was of great interest to the locals and Fresson left Miss Pauer in charge of the plane while he was shown round the locality by Surgeon McClure. They returned to Hooton the following day and had covered over 800 miles and settled most of the joy riding sites. In August of that year, he flew his first paying passengers to Kirkwall and made the acquaintance of James Mckintosh the owner of the Orcadian who was to become one of his biggest supporters. The potential of a Trans-Pentland air service soon became obvious. A modern plane could fly the cross-Pentland journey of thirty-five miles from Wick or Thurso to Kirkwall in twenty minutes. The steamer took four to five hours. The Pentland Firth could be very rough; the air could be much smoother. Provided the traffic density was sufficient, an air ferry couldn’t go wrong. Fresson felt that ‘where there were routes which involved sea crossings, air travel had great possibilities. Fresson had several meetings with the Deputy Town Clerk of Kirkwall and some of his business friends. He told them he was prepared to explore the possibilities, but of course the over-riding consideration was the raising of finance to float an operating company. Up-to-date aircraft would be needed, and airfields would have to be constructed. That would cost a lot. Someone in the group suggested ‘Why not make Inverness your base and fly up the mails which arrive by train from London and the South in the morning? After lunch you would fly the mails South to catch the London express and Glasgow and Edinburgh trains. That would speed up the mails some twenty-four hours. This was a much bigger issue but with more attractive commercial possibilities. Fresson thought that with a mail contract a regular load would always be available and with the mail, why not the newspapers? With a clear plan in his head and the Joy riding season at an end Fresson gave thought to his approach to the GPO. Clearly if he was to generate interest in his proposition, he needed to make the proposal through an established company. Although he intended to start his own company in the Highlands in order to gauge the interest of the GPO, he would need to be represented by the North British Aviation Company. So, in January in 1932 he made his first representations to the Post Office.The North British Aviation Company 1932

On the 5th January 1932 on North British Aviation notepaper, Fresson wrote to the Postmaster General in London. He wrote “Our Mr E. E. Fresson is now in London with a view to establishing an Air Service from Orkney to Inverness and return for the months of May to September. As such a service would operate between Inverness and Kirkwall, touching at Wick in approx. 1 Hour and 15 minutes, we would like to offer facilities for carrying a surcharged mail between these two Cities and for Caithness and Sutherlandshire. Such a service would enable Orkney mail to be replied to and arrive back in Inverness in the same day in order to catch the evening express out for the South from Inverness and which at present takes some three days. We accordingly address this letter to you with a view to requesting the favour of an interview if possible, on Friday next, in order to negotiate this proposal. Would you be so good as to let the writer know if you are prepared to see him c/o Grove End, Northwood, Middlesex. As we are counting on Post Office assistance for contributing to the success of the venture of a first Scottish Air Route, we hope you will be agreeable to giving this matter favourable consideration” Fresson got a reply by return of post offering him an interview with the Director of Postal Services, Brigadier General F. H. Williamson on Friday 8th January. After the meeting of the 8th January Williamson wrote a memorandum on the meeting in which he said “Mr E. E. Fresson of the North British Aviation Co called to see me today. He said that his company is proposing to establish a regular air service during May to September inclusive between Inverness, Wick and Kirkwall. They will have one aeroplane at their disposal with a capacity of about 800 – 900 lbs. The proposal is to leave Inverness at 7 a.m. after the arrival of the train from the South due at 6.30 a.m., call at Wick and arrive at Kirkwall at about 8.10 a.m.. In the afternoon the plane would leave Kirkwall about 5 p.m. and reach Inverness about 6 p.m. Mr Fresson said the Air Ministry were in favour of the scheme, and that a Municipal aerodrome would be provided by the town of Inverness. I said that if a regular air service was established, we would be willing to offer the use of it to the public for the conveyance of mails. There can be no question of sending the whole mail by air, but we could fix a suitable surcharge and advertise the service. The financial results would, of course, depend on the extent to which the public patronise it. As regards payment, Mr Fresson said that he contemplated a charge of about 1sh and 4d per lb. I said that I had not any data to inform him at the moment what the surcharge would be, but that I would look into the question with the idea of fixing a surcharge per packet and will get back with him again on this point.” A second memo looked at the potential benefit of an air service: “The projected air service would give one day’s acceleration for English Mail and say, 4-5 hours gain for Scotch Mail. There is however no delivery between 9.15 a.m. and 6.45 p.m. (except a 4 p.m. delivery on Mondays and Thursdays only) and the Scotch mail would therefore not actually benefit. From Orkney an evening dispatch would be possible instead of a morning dispatch” On the 11th January the PMG wrote to the Air Ministry registering his concerns over the reliability of the proposed service, in particular the Company proposing only to use one aircraft and asked if they had any information on the company and for their views on the matter. The Air Ministry replied on the 28th January, stating that as far as they were aware the Company had 4 Avro 504K’s at their disposal. They advised the PMG that the service should be allowed to mature into fruition and over a period of a fortnight they would assess the reliability of the service. In the meantime, the Ministry would ask the airline to provide details of the scheme and supply reliability statistics. On the 8th February the PMG agreed to hold a decision until the Air Ministry came back with further information. On the 12th February it was prematurely announced in the press that the PMG had authorised Air Mails to the Orkneys, starting in May and to be carried by the North British Aviation Company. The PMG had to assure the Air Ministry that the press releases were unauthorised, and they were still waiting their recommendation. The matter ended on July 2nd when the North British Aviation Company informed the Air Ministry that due to the difficulties of providing an aircraft and getting an Aerodrome site at Inverness in time, they had decided to abandon the project for that year. Clearly, Fresson had no intention of running a service to the Orkney’s through North British Aviation, he was merely setting out his stall for when he had his own Company up and running and was able to provide the service.Highland Airways

Unlike Gandar-Dower who founded Aberdeen Airways in 1935, Fresson did not have access to a large pot of family money. He needed to find financial backers for his scheme to bring it to fruition. After a number of aborted attemps at finance Fresson met with Mr George Law a director of the Scotsman newspaper, who offered him a contract of a year to deliver his newspaper and the money to start the company, that was to be called Highland Airways. This was just what Fresson required, because the newspaper contract along with passengers and a mail contract were what he required for a successful commercial operation. He hoped to float the company later that year but there were still a number of hurdles to overcome. Despite having the finance, he still had nowhere to land the plane in either Inverness of Kirkwall and he still didn’t have a plane suitable for the service. He met with a representative of Inverness council to persuade the council to develop a municipal airfield on Longmans field in Inverness and they readily agreed. and Wick Airfield also went ahead. After stalling with his first choice of an airfield at Hartson in the Orkneys, Fresson found Wideford and struck a deal with farmer who owned the property for a period of five years. Now there was only the aircraft to buy which was to be a Monospar S.T.4 from General Aircraft in Croydon. Unfortunately, there were problems in the development in the plane and it wasn’t ready for September 1932. They finally collected the plane in April 1933 and with Highways Airways registered they were ready to begin the new service.The New Service Starts – 8th May 1933

On a perfect May morning, Provost MacDonald and his wife officiated at the proceedings on behalf of the Town Council. With a bottle of whiskey in place of the traditional champagne, Mrs McDonald christened the plane Inverness.The Provost said ‘This is a unique occasion in the history of transport in the Highlands. It will bring the remotest part of Scotland to the front door. I wish the service every success’. The bottle crashed on the propellor on one of the motors and liberally sprinkled it with the ‘Dew of the Islands’. The plane left Inverness at 10 a.m. and arrived at Wick at 10.50. It left Wick at 10.55 and arrived at Kirkwall at 11.20. On the return it left Kirkwall at 2.10 p.m arriving at Wick at 02.35 departing again at 2.40. It arrived in Inverness at 15.30. The fare each way was £2.50 to Wick and £3 to Kirkwall.Securing an Air Mail Contract.

Historically, it has often been written that the reason why there was over a year between the start of the Highland Airways scheduled service starting and the issuing of a mail contract was that the Post Office required a year’s reliable flying before they committed themselves. This mistaken idea appears to have come from Fresson himself, when he mentioned in his autobiography ‘Air Road to the Isles’ that Williamson in his initial meeting with Fresson had said ‘Send us regularity figures for a year’s operations and we will consider a contract if they are good enough’. It is most unlikely that Williamson said such a thing as he does not mention it in his own notes of the meeting, and it is never mentioned in any correspondence between the Post Office and the Airline. Not once. There is no denying that the Post Office required airlines to prove their reliability before issuing a contract, but this was done through the Air Ministry who would monitor an Airlines reliability statistics and report back to the Post Office with a recommendation. The Post Office would never produce an arbitrary time scale for assessing reliability. The main issue was how to fund the service. The P.O. accepted it would be to great advantage but at that time airmails were sent with a surcharge and it was expected this was how the service would work. Some investigations were done and it was reported that “The service is primarily for the Orkney Islands and its effect on Caithness cannot yet be properly gauged. I am of the opinion however that Air Mail Services will not be largely taken advantage of, supposing an Air letter service was started. No doubt there are a few who would take advantage of the services but there would be no large volume of business done”.

Articles - The First GB Internal Airmail Contract

Copyright

© 2020 Robert Farquharson All Rights Reserved

British Internal Airmails of the 1930’s

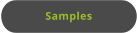

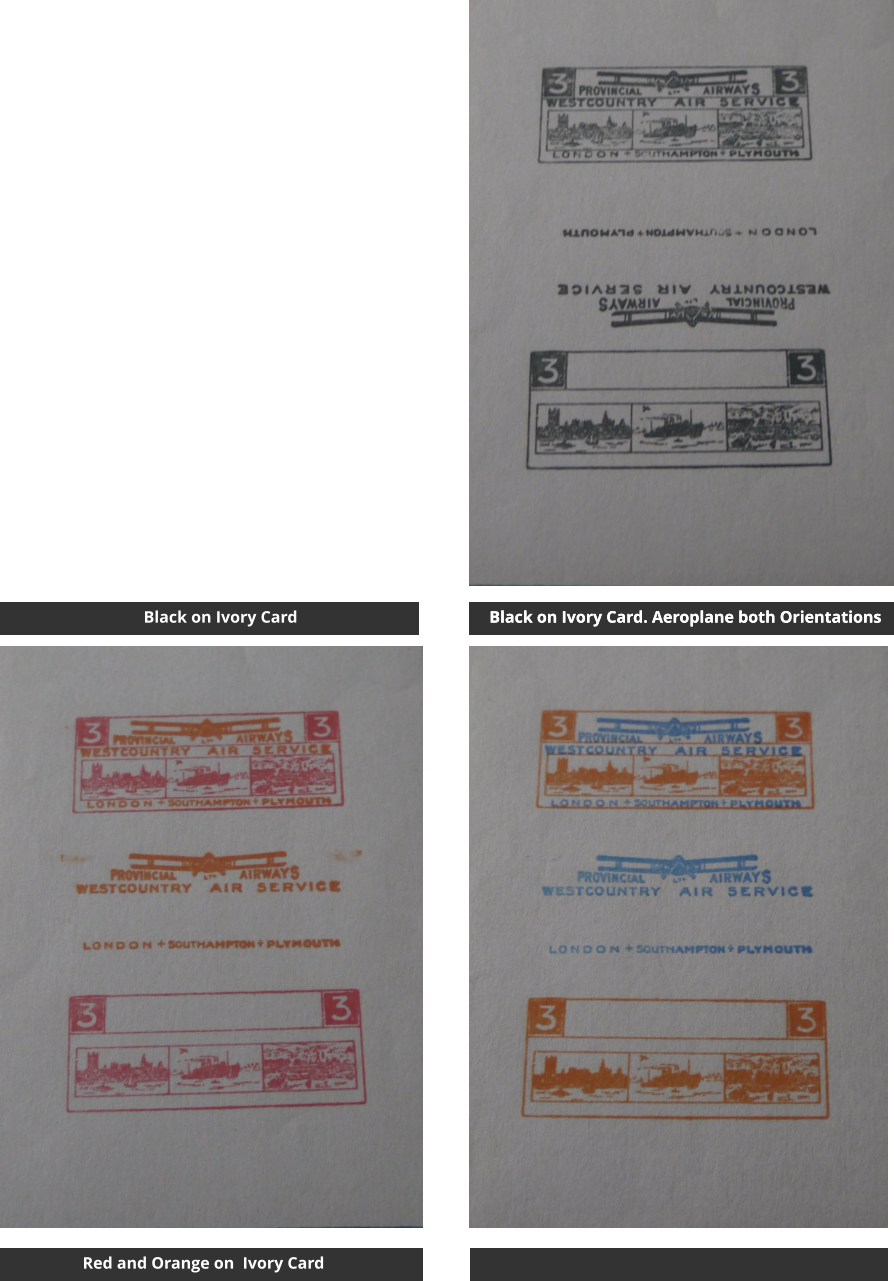

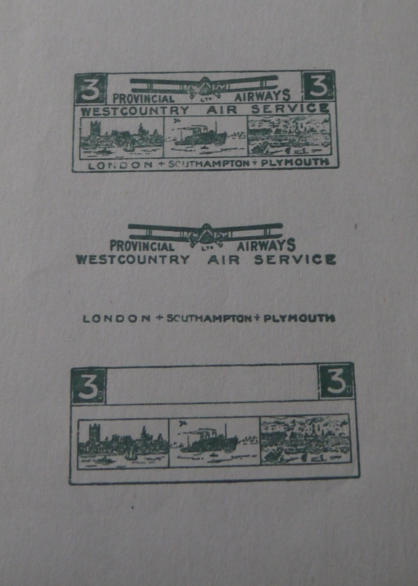

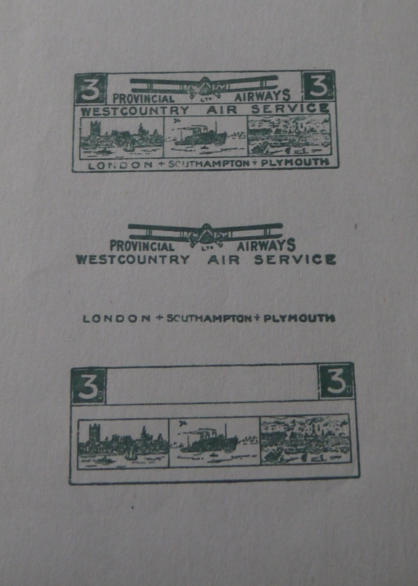

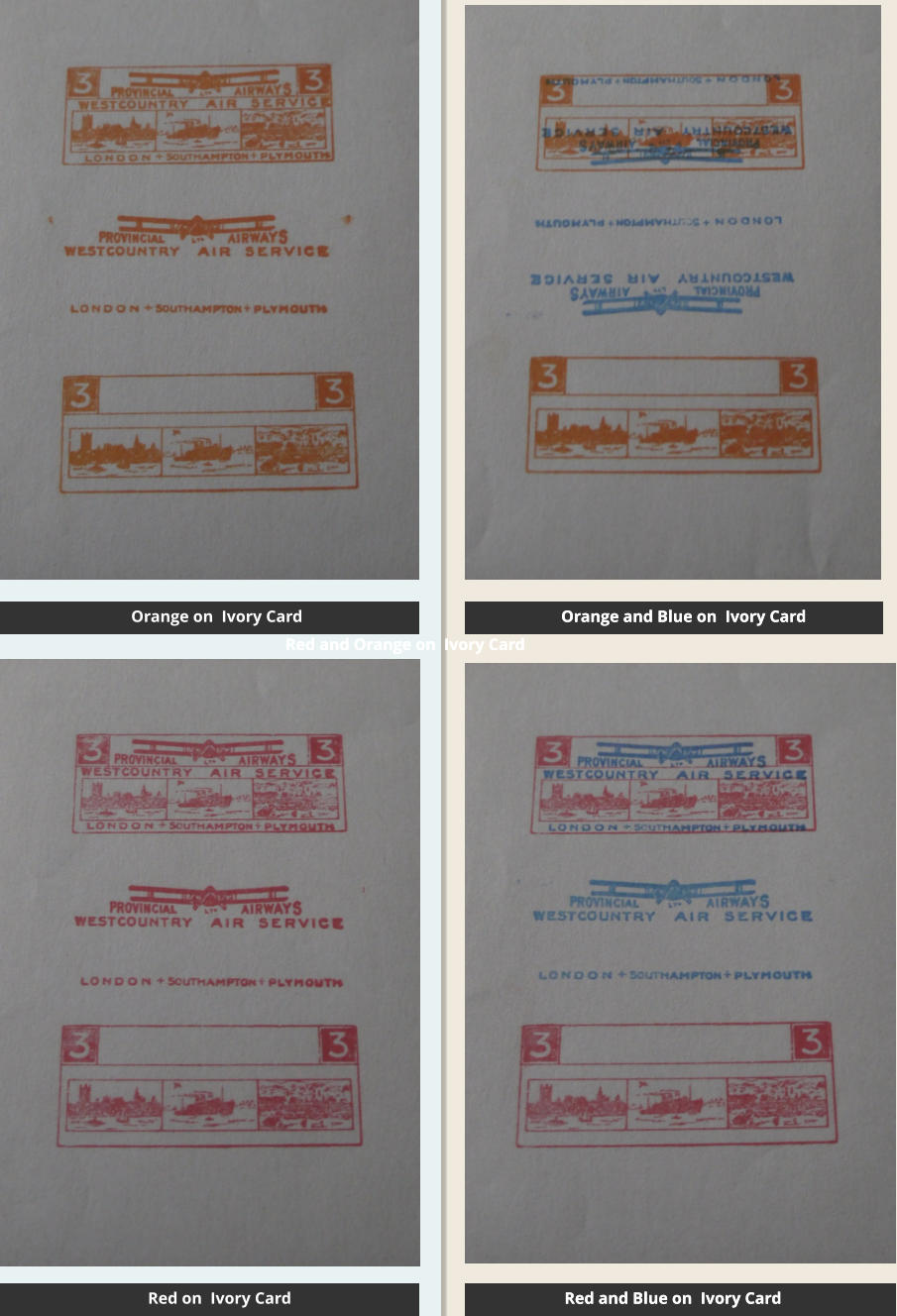

Section 5 - Directors Samples

These were printed to submit to the Directors of Provincial Airways to select the final colour combination. Some were put through the press the wrong way round which therefore created an inverted vignette. The errors were thought to have been leaked onto the philatelic market and were not destined for the powers that be. [**NOTE** I suspect this is incorrect. The samples did appear on the market, but they were probably not leaked. The inverted vignette may have been an initial accident, but there were far too many printed for them all to be accidents. I suspect the directors saw the potential in selling these to collectors. In the end they were packaged in packets and sold. (Francis Field). How they were first marketed is not known, but now they are sold as proofs when they are no such thing.]

Blue on Ivory Card

Blue on Ivory Card